1. This matcha (in its finished state) is not something I keep sitting around in stock. I want to ensure the customer receives the highest quality I am able to provide, thus the matcha will be ground to order.

2. It will take me approximately 10 hours of pushing a 25lbs granite stone around in a circle to grind one order of this matcha.

3. It is sold and presented in a Japanese lacquerware ‘natsume’ tea caddy.

4. 20g of matcha can prepare approximately 10 bowls of thin matcha (usucha) or 5 bowls of thick matcha (koicha). It’s somewhat rare that one matcha can produce a remarkable version of both preparation styles, but I wholeheartedly believe this can.

5. This matcha is a mono-cultivar product based on the bush called Gokou. Gokou is highly fragrant and unorthodox in flavor compared to most other matcha cultivars in use. It stands out in a way I believe a connoisseur can deeply appreciate, especially when served as koicha.

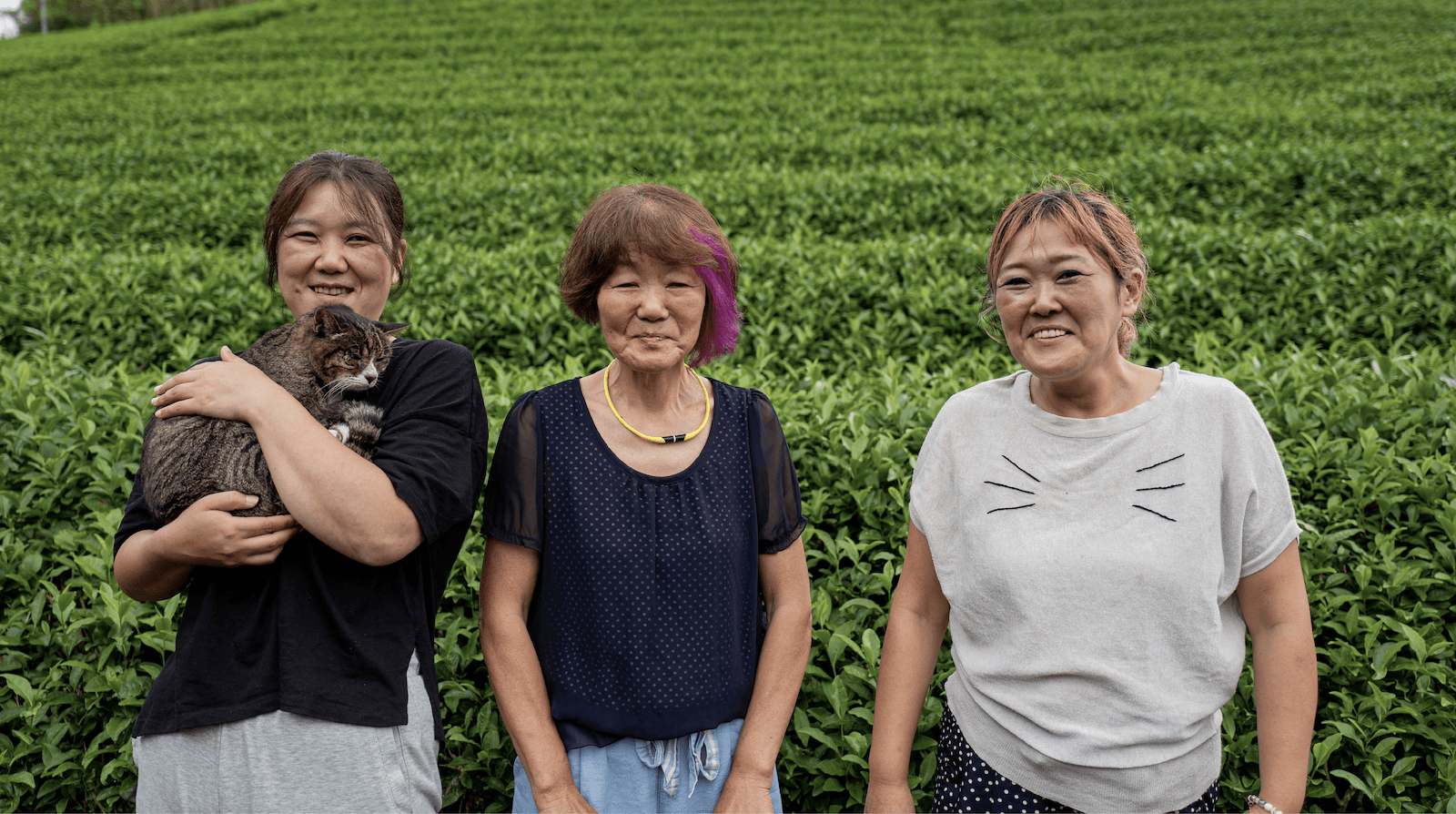

6. This matcha comes from Kiroku-En, a small women-run farm in Wazuka, Kyoto that I had a chance to visit in October 2022.

7. SaKa is a name with importance to me, it’s a nickname I’ve given this tea that will have no relevance to anyone else, but I will explain it below.

Why grind it by hand?

There are very few shops in the world that offer hand-ground matcha for sale. I’ve actually never even seen one, and when I asked the group of Japanese tea connoisseurs that I’m part of if they knew of any, there was nothing — a few replies about small scale stone-milled stuff but nothing hand-ground. I am confident that somewhere in the elite circles of Japan, hand-ground matcha is prepared for customers engaging in a very authentic and bespoke tea ceremony, though for regular folks it’s totally off the radar.

In principle, if I am able to convince you that effort, passion, and love have a flavor, that is the reason to why I have decided to grind matcha by hand. I believe that if my mothers chocolate chip cookie recipe was given to a kitchen robot in the future, it would not taste the same as she makes it. By all accounts, the kitchen robot should outperform my mom in every aspect, but it doesn’t love me, and I don’t respect its effort or the time it spent to make the cookies for me. You, the person reading this might not know me, you might not respect, love, or even care about me, but know this: if you buy this matcha from me, I cherish you, I respect you, and during every minute of this 10 hour grind, my muscles aches and pains will be in your honour, and I will give you the best product I can.

About 2 years ago I made a commitment to a mentality, ‘slow down’. Our lives are flying by before our eyes. My daughter just turned 11; I’m 35. Can I have a real impact on this world? Maybe not, but I bet I can give you goosebumps as you drink a bowl of this koicha, I’ve accepted that, and it’s enough for me.

If you’re a matcha lover, you may have seen an emphasis on the term ‘stone-milled’ used by the shops you visit. Using a stone mill is the traditional way to grind tea into powder, they have been used since the 1500s at the very least, but probably much earlier. They’re great — they can grind tea leaves to 5-10 microns in size, so fine that you can split the chloroplasts open and see the beautiful bright green colour they hold inside. 5 microns is about 8 times finer than the pollen in the air, to give a sense of scale.

This is a video of what ‘stone milled’ means.

and this is what ‘hand ground’ means

The precise reason I chose to invest in matcha and grind it with my physical strength is the notion that machines can never replicate the intangible flavor of effort; and that while I am still young, I can do my part to keep this culture alive.

If you’re a fan of matcha and have the means to purchase one of these, please know that despite being across the world from its source, there are very few opportunities you will have in life to try something like this. This is a very real experience.

The Region, Farmers, and Tea Bush

Kiroku-En is the name of the company that the tencha used in this matcha comes from. I made a video of the time I spent there. I only met Hori-san once (that’s her on the right) but we’ve kept in touch on Instagram since then. Ian (from Yunomi.life) and I met her at her quaint little house on Wazuka river and took her Suzuki Lapin up the mountain to her families tea field.

https://kirokuen.com/ is their website, you can learn a bit more about them and their philosophy about tea there!

To fully appreciate what matcha is we must start with understanding ‘tencha’. Tencha is an unrolled green tea that grew for a significant period of time under forced shade. Shortly after harvesting from the bushes, the leaves are steamed and dried. After drying, they have their stems and veins removed so that only flakes of green leaf lamina remain. The result has a similar appearance to dried basil or parsley flakes. By contrast, gyokuro (Japan’s other famous shade grown tea) undergoes the same growing conditions and steaming as tencha but goes through a damaging rolling process afterwards to create green leaf volatiles for the aroma. After the rolling it is shaped into a needle-like form before drying, this shape is typical of Japanese tea, and quite different looking than tencha.

Can I compare tea to paint for a second? There are many tea bushes (paints) out there, but to make excellent matcha (a finished painting) only a few seem to be used. Asahi and Gokou are probably the two front runners ahead of things like Okumidori, Yamatomidori, Samidori, Saemidori, Kanayamidori, Ujimidori, Okuyutaka, and Yabukita.

Generally an artist (matcha creator) will put different colors of paint on their palette to create a vivid picture of their imagination. Browns, greens, greys, blacks. It depends on how literal or abstract the artist wants to be, a fantastic ink brush (sumi-e) painting may only need black, while attempting hyper-realism may require several blends of colour. The famous matcha teas from the shops of Japan are rarely just one cultivar of the tea bush. They are a palette with 2 to 5 colors, expertly blended in proportion to produce a painting unique to their shop and taste, of course the blend would be a proprietary secret.

If an artist would rely on one colour for their painting, they must have faith in their product, in its vibrancy, in its consistency, in its range of saturation. As I said in the points in the beginning of this article, there are 2 traditional preparation styles of matcha — usucha and koicha (thin and thick matcha). You can think of usucha as the lower area along each strip of the color chart, while koicha is the upper area. In reality, usucha is matcha drank at a strength of 1g tea to 30g water (1:30) and whisked to develop a frothy foam surface, while koicha is three times stronger at (1:10) and gently mixed without the froth. Koicha resembles a dark green paint and is something that matcha drinkers don’t tend to discover unless they fall down the rabbit hole.

In my opinion, colors 1, 5, 13, 16, and 18 are the ‘best’. You could use color 3 in a painting but it will never be as saturated as color 1 BUT you can dilute color 1 to create color 3, it’s a one way street, and that quality makes color 1 superior in my eyes.

The same principle goes for 5 and 7. Of the 20 swatches on display here, 13 is remarkable for being brighter than the rest, 16 that it stays saturated for such a long period, and 18 is remarkable for the range of colour that it displays.

Asahi cultivar matcha is on average most like #6 to me. Gokou is like #18. What I mean by this is whether usucha or koicha, asahi remains a consistent shade of green fragrance you can make a saturated or diluted version of more or less the same color. The colour is green, its unmistakable, it’s unshakable, and that’s why it wins competitions so often. Gokou is often used in a composition because LOOK AT THAT SCARLET RED, you only need very little of a color like that in an overall picture to make it a focal point. We’re talking about aroma here folks, and the concept that aromas have colors as characterized by synasthesia. By painting with both 6 and 18, think of the possibilities! I have made many matcha blends in my life that create a mental composition of fragrance and flavor that would allow the drinker to close their eyes and wander my aroma landscape. I’m not done with creating these blends but I’m at a stage in life that developing a deeper understanding of the fundamentals that each tencha can bring to my palette is more important than what I can do with them. It’s also inspiring for people to see things like 18 on their own, to see what gokou can do by itself. How red the aroma is! Of course like all matcha, gokou is visually a beautiful shade of green, but if you brewed a bowl of gokou matcha, closed your eyes and slowly inhaled its fragrance, mentally you would be transported to a gravelly trail-head beneath 1000 pines, with a fragrant wind blowing towards you carrying a saturated red aroma reminiscent of strawberries, raspberries, and red currants together as a puree.

What is ceremonial matcha and how is it different from culinary matcha, or competition grade matcha?

Ceremonial matcha is matcha that should be of a suitable quality to use in the tea ceremony, when the preparation is concentrated and consists of just matcha and water. It’s a loose lawless term; where as culinary matcha admits inferiority in a sense that the matcha may be too bitter, sour, or astringent to enjoy straight, but could be utilized in recipes to give dishes a basic matcha flavor. Not all culinary matcha is undrinkable, and not all ceremonial matcha deserves the designation it was given. To each their own, these are just labels to help steer customers into a product they want to buy. Competition grade matcha should harbour a higher expectation and deliver on it. We should differentiate that competition grade tencha exists, as does competition grade matcha. Competition grade tencha would mean the potential of the cultivar that created it is of the highest calibre, but as I said in the analogy above, it’s still just one colour of paint. A competition grade of matcha created using competition grades of tencha, by the most skilled blender in the world, would surely create the ultimate matcha. If I created one of the blends I was referring to in the section above (that you could delve deeper into here), that would be competition grade matcha — a fantasy landscape created with purpose that can captivate the minds of drinkers. Competition grade is just another label, and it’s also unregulated, so it should be treated with the same amount of consideration as the terms ceremonial or culinary.

The nickname ‘SaKa’

1) As we do in Japan, we make long names short. Sachio and Kazuko, the names of my parents in-law, two people I love very much — SaKa seemed a fitting name for a product I’ll honour their existence with.

2) When I turned 21 or 22, and was a butler for the Japanese consulate, one of my coworkers Tetsu wrote a poem on my birthday card. We were close colleagues in the beginning of his contract, but eventually had a big falling out. He surely didn’t want to sign my card, but the consulate general’s wife forced him. All of the house staff were forced to sit together and celebrate my special day with some cake and tea. On the card he wrote (translated to english)

In Life there are 3 hills (3 saka)

Up hill (ue saka)

Down hill (shita saka)

masaka (translates as ‘no way!’ with connotations like unbelievable, impossible, it can’t be done!)

He said I would understand the poem one day, and implied I was too ignorant about life to get it then. He wanted me to quit so badly, and he surely wondered why despite him making my work life hell, that I endured it. He had to leave Canada eventually and I carried on there for several more years. That poem I never forgot. I interpret it as ‘in life there are easy times and hard times, but sometimes you just have to give up and move on because you just can’t do it.’

3) The ‘saka’ of Osaka 大阪 — home to one of my favourite places in the world, a pedestrian overpass above a busy street right next to Osaka Station. It was here that I first truly witnessed something that I think is impossible to see in Canada, it never even occured to me that I might see such a thing in the world. A landscape without life. No birds, no trees, no grass or shrubs. Just concrete, metal, electricity and humans — so many humans. This doesn’t necessarily sound like a good thing, but it was a hugely impactful scene for me to see when I was 18. It really shaped my opinion of what a super-city is or can become, for better or worse.

If my SaKa matcha is something you just wanted to try, I would be willing to grind, prepare, and serve a bowl of usucha for $60, or a bowl of koicha for $120 to you at Carino during a visit, or as part of an event that we create together (see events tab at the top of the page). I just need to have some advanced notice to work the grinding time into my life. Although it is a less expensive option in total, it’s comparatively so much less value for your money than buying the 20g in the lacquerware tea caddy; but it’s what I must ask for. Starting from an empty mill it takes about 1.5 hours before any usable tea comes out, and another hour and a half for a bowl of usucha or 3 hours for a bowl of koicha. What remains trapped within the grooves of the mill after I am finished is not suitable to use as it has not been ground fine enough, it’s essentially a waste product. So I grind for either 5 hours to make 4g or 10 hours to make 20g. If you buy 20g I’d be happy to make it for you during your visit at no charge using your product, it might work out better that way.